Governance Models That Don’t Scale: The World According to Charles T. Munger and Jean Jacques Rousseau

Can you name five benign dictators who have ruled successfully for any meaningful period of time (non-fiction)? Can you name five successful, long serving CEO’s (excluding Warren Buffett) whose governance histories are free of the “high-beta” associated with outliers such as Larry Ellison and Steve Jobs?

It’s not easy. Why? Because enlightened dictators and their corporate CEO equivalents are very, very rare; maintaining immunity to the intoxicating effects of power challenges basic human nature.

It is in this context that I found “Corporate Governance According to Charles T. Munger”, a brief article from the Stanford Closer Look Series, thought provoking if not practical. The article was written by David Larker, Director of the Corporate Governance Research Program at the Stanford Graduate School of business, and Brian Tayan, a researcher with Stanford’s Corporate Governance Research Program.

The authors summarize and explain Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charles T. Munger’s unorthodox view of a model for corporate governance. According to the article, Munger believes that corporations and their boards should empower their CEO’s more, not less. Munger’s effective CEO, modeled, of course, on Warren Buffet, should be unencumbered by rigid process and freed of unnecessary, excessive checks and balances. Why? So that the CEO can lead effectively. How? In Munger’s construct, CEO’s police themselves, holding themselves accountable to their loosely overseeing directors by binding themselves to a trust based system. And corporate directors should reward these CEO’s for creating shareholder value, while deliberately underpaying them in terms of their annual salary-based cash compensation. According to Munger, and as quoted in the article:

“Good character is very efficient. If you can trust people, your system can be way simpler. There’s enormous efficiency in good character and dis-efficiency in bad character … We want very good leaders who have a lot of power, and we want to delegate a lot of power to those leaders…The highest form that civilization can reach is a seamless web of deserved trust—not much procedure, just totally reliable people correctly trusting one another.”

I agree with Mr. Munger completely, while asking the same questions raised by the authors at the end of this article:

“The trust-based systems that Munger refers to tend to be founder-led organizations. How much of their success is attributed to the managerial and leadership ability of the founder, and how much to the culture that he or she has created? Can these be separated? How can such a company ensure that the culture will continue after the founder’s eventual succession?”

Unfortunately, and founders notwithstanding, the collective global capitalist experience since private property rights were invented and enforced has shown that there aren’t enough of those people on this planet.

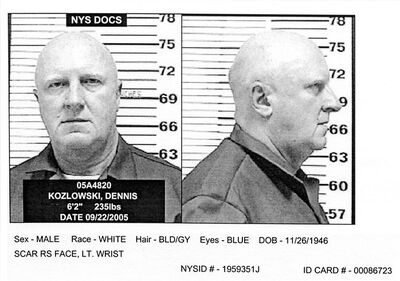

For a specific cautionary example, I am reminded of Tyco International and its former CEO, Dennis Kozlowski. Kozlowski was recently paroled, almost twelve years after his indictment, ultimate conviction, and after serving over eight years in Attica, for a $134 million corporate fraud (this amount represents a small fraction of the losses suffered by public shareholders). The disgraced former directors of Tyco International (vintage 1999), seemingly highly trustworthy and accomplished men and women, also come to mind. This group, along with the enterprise builders at Enron, Worldcom, and Adelphia, to name just a few, are at the top of my list of examples of poor corporate stewardship and help explain why Mr. Munger’s model for corporate governance is still-born.

But I did say the article was thought provoking, as Charles Munger’s corporate governance philosophy, in my view, evokes Jean Jacques Rousseau’s concept of the Lawgiver. Author Alex Scott summarizes Rousseau’s core thesis from the Social contract succinctly in this excerpt from his book, The Conditions of Knowledge: Reviews of 100 Great Works of Philosophy :

“The general will always desires the common good, says Rousseau, but it may not always choose correctly between what is advantageous or disadvantageous for promoting social harmony and cooperation, because it may be influenced by particular groups of individuals who are concerned with promoting their own private interests. Thus, the general will may need to be guided by the judgment of an individual who is concerned only with the public interest and who can explain to the body politic how to promote justice and equal citizenship. This individual is the “lawgiver” (le législateur). The lawgiver is guided by sublime reason and by a concern for the common good, and he is an individual whose enlightened judgment can determine the principles of justice and utility which are best suited to society.”

I agree! Let’s find that individual and give him (or her) the keys to the public policy car! Munger’s corporate lawgiver, the enlightened CEO, is also an admirable model worth aspiring to emulate.

As with Rousseau’s 1762 treatise, history has sadly shown us that we lack sufficient incorruptible raw material across the entire history of mankind to render the “lawgiver” experiment successfully scalable, be it in public government or corporate governance.

The unbridled exercise of power is the ultimate intoxicant, and very few humans can responsibly limit the flow of that drug, especially not when they have are given the opportunity to administer it to themselves.

For a specific cautionary example, I am reminded of Tyco International and its former CEO, Dennis Kozlowski. Kozlowski was recently paroled, almost twelve years after his indictment, ultimate conviction, and after serving over eight years in Attica, for a $134 million corporate fraud (this amount represents a small fraction of the losses suffered by public shareholders). The disgraced former directors of Tyco International (vintage 1999), seemingly highly trustworthy and accomplished men and women, also come to mind. This group, along with the enterprise builders at Enron, Worldcom, and Adelphia, to name just a few, are at the top of my list of examples of poor corporate stewardship and help explain why Mr. Munger’s model for corporate governance is still-born.

But I did say the article was thought provoking, as Charles Munger’s corporate governance philosophy, in my view, evokes Jean Jacques Rousseau’s concept of the Lawgiver. Author Alex Scott summarizes Rousseau’s core thesis from the Social contract succinctly in this excerpt from his book, The Conditions of Knowledge: Reviews of 100 Great Works of Philosophy :

“The general will always desires the common good, says Rousseau, but it may not always choose correctly between what is advantageous or disadvantageous for promoting social harmony and cooperation, because it may be influenced by particular groups of individuals who are concerned with promoting their own private interests. Thus, the general will may need to be guided by the judgment of an individual who is concerned only with the public interest and who can explain to the body politic how to promote justice and equal citizenship. This individual is the “lawgiver” (le législateur). The lawgiver is guided by sublime reason and by a concern for the common good, and he is an individual whose enlightened judgment can determine the principles of justice and utility which are best suited to society.”

I agree! Let’s find that individual and give him (or her) the keys to the public policy car! Munger’s corporate lawgiver, the enlightened CEO, is also an admirable model worth aspiring to emulate.

As with Rousseau’s 1762 treatise, history has sadly shown us that we lack sufficient incorruptible raw material across the entire history of mankind to render the “lawgiver” experiment successfully scalable, be it in public government or corporate governance.

The unbridled exercise of power is the ultimate intoxicant, and very few humans can responsibly limit the flow of that drug, especially not when they have are given the opportunity to administer it to themselves.